Originally published by To The Source:![]() www.tothesource.org/8_7_2014/8_7_2014.htm

www.tothesource.org/8_7_2014/8_7_2014.htm

Twentieth century missionary, Lesslie Newbigin describes best the relationship between the Christian worldview and others: "The Christian claim is that though the Christian worldview can in no way be reached by any logical step from the axioms of [the other worldviews], nevertheless the Christian worldview does offer a wider rationality that embraces and does not contradict the rationality of [these other worldviews]."

C.S. Lewis' picture of this is that "man is a tower in which the different floors can hardly be reached from one another but all can be reached from the top floor."

This does not mean Christians are necessarily smarter than non-Christians but that every one who comes to Christ has access to a higher rationality, having access to the mind of Christ. It also means, as was my experience, that people without Christ do not have access to particular levels of rationality (Romans 1:18-22). In Biblical terms minds and hearts become darkened. This dullness of mind is experienced when unbelievers consider particular facts about the gospel, which to them appear foolish and become stumbling blocks. They wonder how Christians can otherwise seem so reasonable when these things seem so irrational.

Newbigin describes this conflict in terms of the resurrection: "The community of faith makes the confession that God raised Jesus from the dead and that the tomb was empty thereafter. Within the plausibility structure of the world this will become something like the following: The disciples had a series of experiences that led them to the belief that, in some sense, Jesus was still alive and therefore to interpret the cross as victory and not defeat. This experience can be accepted as a fact. People do have such psychological experiences. If this is what is meant by the Easter event it qualifies for admission into the world of fact. The former statement (i.e., that the tomb was empty) can be accepted as a fact only if the whole plausibility structure of contemporary Western culture is called into question."

Christ calls his people to radically challenge the plausibility structures of the world just as he did. This is why it is critical that we fully understand the principles and cultural manifestations of these plausibility structures or worldviews. Otherwise our only option is to compromise by giving into the cultural elite's insistence that we all function only with secular norms. However, not having any permanent moral guardrails, these norms easily morph over time. Giving into the dominant power of secularism makes us complicit in the cultural tendency to limp along using solely the lowest common denominator of human reason – secular reason.

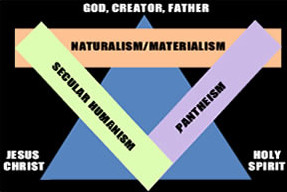

The diagram is a rough sketch of the four global worldviews discussed in previous posts. Outside the triangle lie the principles of secular humanism, naturalism and pantheism that are distortions of truth caused by the addition of false principles, such as secular humanism's utopian vision of human reason, or naturalism's insistence that everything is material, or pantheism's amorphous spiritual ennui. All of these worldviews and their standing philosophies, methods and theories share some principles with Christianity depicted as their intersection with the triangle. According to Judeo-Christian principles, evil cannot create; it can only distort. It would not be possible for any worldview to stand if it did not contain some truth (inside the triangle).

Christianity is the one worldview that actually encompasses the true and reasonable principles of all three other worldviews and much more.

The Trinity holds all things together defining truth's boundaries; it is the ultimate gravitational force of physical, natural and spiritual reality. For example, the truths of naturalism and pantheism, generally irreconcilable, are actually reconciled inside the triangle; they are part of the same totality. In its independent form scientific naturalism ultimately excludes the possibility of spiritual transactions, which makes spiritual knowledge both unnecessary and inaccessible. Pantheism in its most orthodox form proposes the world is ultimately an illusion, which makes science both unnecessary and impossible. Christ's teachings unify the spiritual, natural and human worlds.

Here it is possible to study the interactions of spiritual and

natural phenomena. For example, in the work of Orthodox theologian

![]() Jean-Claude Larchet on illness, he points out the importance of considering the

spiritual dimension of human beings when seeking to alleviate their

physical ailments.

Jean-Claude Larchet on illness, he points out the importance of considering the

spiritual dimension of human beings when seeking to alleviate their

physical ailments.

Thus, Christianity gives us science without materialism (scientism) – a science with a conscience, not floating in mid air as a servant to the latest and most popular human urges. It gives us humanism also tethered to a permanent moral code that undergirds human flourishing without rationalizing every human desire. Lastly, Christianity gives us spirituality with purpose, and sin with redemption and restoration. It is the only safe route to true self-knowledge since there is a viable solution to what we find in ourselves. The Judeo-Christian framework builds spiritual discernment in a world that has both good and evil, and provides the means to fight the evil and expand the good – first, in our own selves and, second, in our culture. From inside the triangle we are not blind men surveying the elephant, each discerning the universe from our limited worldviews. Inside the triangle the whole picture emerges of the coherent unity of all truth – in Christ all things are held together. This unity of true knowledge was the initial impetus for the modern university.

For a half a century, Western intellectuals predicted the demise of the religious and the emergence of a grand secular age based solely on human reason. David Bentley Hart notes that "either human reason reflects an objective order of divine truth or human reason is merely the instrument and servant of the will." Today prominent philosophers (even atheists) refer to the 21st Century as post-secular.

God's rationality encompasses and surpasses that of the world. In some cases it is almost the opposite of our own instincts. Take for example that God chose Peter, a rough uneducated fisherman to take the Gospel to the highly educated Jews; and the refined, well educated Paul to take the Gospel to the rough pagan Greeks. Though great philosophers and theologians have examined and rearticulated the words of Jesus for two thousand years, Jesus taught with words that even children could understand. God's rationality is simply all comprehensive, all true and brilliantly transformative.